Architecture Components

Nowadays, Microservices is one of the most popular buzz-words in the field of software architecture. There are quite a lot of learning materials on the fundamentals and the benefits of microservices.

Monolithic Architecture

Enterprise software applications are designed to facilitate numerous business requirements. Hence a given software application offers hundreds to functionalities and all such functionalities are piled into a single monolithic application. For examples, ERPs, CRMs and other various software systems are built as a monolith with several hundreds of functionalities. The deployment, troubleshooting, scaling and upgrading of such monstrous software applications is a nightmare.

Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) was designed to overcome some of the aforementioned limitations by introducing the concept of a ‘service’ which is an aggregation and grouping of similar functionalities offered from an application. Hence, with SOA, a software application is designed as a combination of ‘coarse-grained’ services. However, in SOA, the scope of service is very broad. That leads to complex and mammoth services with several dozens of operations(functionalities) along with complex message formats and standards (e.g: all WS* standards).

Figure 1 : Monolithic Architecture

In most cases, services in SOA are independent of each other, yet they are deployed in the same runtime along with all other services (just think about having several web application which is deployed into the same Tomcat instance). Similar to monolithic software applications, these services have a habit of growing over time by accumulating various functionalities. Literally, that turns those applications into monolithic globs which are no different from conventional monolithic applications such as ERPs. Figure 1 shows a retail software application which comprises of multiple services. All these services are deployed into the same application runtime. So its a very good example of a monolithic architecture. Here are some of the characteristics of such applications which are based on monolithic architecture.

Monolithic applications are designed, developed and deployed as a single unit.

Monolithic applications are overwhelmingly complex; which leads to nightmares in maintaining, upgrading and adding new features.

Hard to practice agile development and delivery methodologies with Monolithic architecture.

It is required to redeploy the entire application, in order to update a part of it.

Scaling : Has to be scaled as a single application and difficult to scale with conflicting resource requirements (e.g: one service requires more CPU while the other requires more memory)

Reliability — One unstable service can bring the whole application down.

Hard to innovate : Its really difficult to adopt new technologies and frameworks as all the functionalities has to build on a homogeneous technologies/frameworks.

These characteristics of Monolithic Architecture has led to the Microservices Architecture.

Microservices Architecture

The foundation of microservices architecture(MSA) is about developing a single application as a suite of small and independent services that are running in its own process, developed and deployed independently.

In most of the definitions of microservices architecture, it is explained as the process of segregating the services available in the monolith into a set of independent services. However, in my opinion, Microservices is not just about splitting the services available in monolith into independent services.

The key idea is that by looking at the functionalities offered from the monolith, we can identify the required business capabilities. Then those business capabilities can be implemented as fully independent, fine-grained and self-contained (micro)services. They might be implemented on top of different technology stacks and each service is addressing a very specific and limited business scope

Therefore, the online retail system scenario that we explain above, can be realized with microservices architecture as depicted in figure 2. With the microservice architecture, the retail software application is implemented as a suite of microservices. So as you can see in figure 2, based on the business requirements, there is an additional microservice created from the original set of services that are there in the monolith. So, it is quite obvious that using microservices architecture is something beyond the splitting of the services in the monolith.

Figure 2 : Microservice Architecture

So, let’s dive deep into the key architectural principles of microservices and more importantly, let’s focus on how they can be used in practice.

Designing Microservices : Size, scope and capabilities

You may be building your software application from scratch by using Microservices Architecture or you are converting existing applications/services into microservices. Either way, it is quite important that you properly decide the size, scope and the capabilities of the Microservices. Probably that is the hardest thing that you initially encounter when you implement Microservices Architecture in practice.

Let’s discuss some of the key practical concerns and misconceptions related to the size, scope and capabilities of microservices.

Lines of Code/Team size are lousy metrics: There are several discussions on deciding the size of the Microservices based on the lines-of-code of its implementation or its team’s size (i.e. two-pizza team). However, these are considered to be very impractical and lousy metrics, because we can still develop services with less code/with two-pizza-team size but totally violating the microservice architectural principals.

‘Micro’ is a bit misleading term : Most developers tend to think that they should try make the service, as small as possible. This is a mis-interpretation.

In the SOA context, services are often implemented as monolithic globs with the support for several dozens of operations/functionalities. So, having SOA-like services and rebranding them as microservices is not going to give you any benefits of microservices architecture.

So, then how should we properly design services in Microservices Architecture?

Guidelines for Designing microservices

Single Responsibility Principle(SRP): Having a limited and a focused business scope for a microservice helps us to meet the agility in development and delivery of services.

During the designing phase of the microservices, we should find their boundaries and align them with the business capabilities (also known as bounded context in Domain-Driven-Design).

Make sure the microservices design ensures the agile/independent development and deployment of the service.

Our focus should be on the scope of the microservice, but not about making the the service smaller. The (right)size of the service should be the required size to facilitate a given business capability.

Unlike service in SOA, a given microservice should have a very few operations/functionalities and simple message format.

It is often a good practice to start with relatively broad service boundaries to begin with, refactoring to smaller ones (based on business requirements) as time goes on.

In our retail use case, you can find that we have split the functionalities of its monolith into four different microservices namely ‘inventory’, ‘accounting’, ‘shipping’ and ‘store’. They are addressing a limited but focussed business scope, so that each service is fully decoupled from each other and ensures the agility in development and deployment.

Messaging in Microservices

In monolithic applications, business functionalities of different processors/components are invoked using function calls or language-level method calls. In SOA, this was shifted towards a much more loosely coupled web service level messaging, which is primarily based on SOAP on top of different protocols such as HTTP, JMS. Webservices with several dozens of operations and complex message schemas was a key resistive force for the popularity of web services. For Microservices architecture, it is required to have a simple and lightweight messaging mechanism

Synchronous Messaging — REST, Thrift

For synchronous messaging (client expects a timely response from the service and waits till it get it) in Microservices Architecture, REST is the unanimous choice as it provides a simple messaging style implemented with HTTP request-response, based on resource API style. Therefore, most microservices implementations are using HTTP along with resource API based styles (every functionality is represented with a resource and operations carried out on top of those resources).

Figure 3 : Using REST interfaces to expose microservices

Thrift is used (in which you can define an interface definition for your microservice), as an alternative to REST/HTTP synchronous messaging.

Asynchronous Messaging — AMQP, STOMP, MQTT

For some microservices scenarios, it is required to use asynchronous messaging techniques(client doesn’t expects a response immediately, or not accepts a response at all). In such scenarios, asynchronous messaging protocols such as AMQP, STOMP or MQTT are widely used.

Message Formats — JSON, XML, Thrift, ProtoBuf

Deciding the most suited message format for Microservices is a another key factor. The traditional monolithic applications use complex binary formats, SOA/Web services-based applications use text messages based on the complex message formats(SOAP) and schemas(xsd). In most microservices based applications use simple text based message formats such as JSON and XML on top of HTTP resource API style. In cases, where we need binary message formats (text messages can become verbose in some use cases), microservices can leverage binary message formats such as binary Thrift, ProtoBuf or Avro.

Service Contracts — Defining the service interfaces — Swagger, RAML, Thrift IDL

When you have a business capability implemented as a service, you need to define and publish the service contract. In traditional monolithic applications we barely find such feature to define the business capabilities of an application. In SOA/Web services world, WSDL is used to define the service contract, but as we all know WSDL is not the ideal solution for defining microservices contract as WSDL is insanely complex and tightly coupled to SOAP.

Since we build microservices on top of REST architectural style, we can use the same REST API definition techniques to define the contract of the microservices. Therefore microservices use the standard REST API definition languages such as Swagger and RAML to define the service contracts.

For other microservice implementation which are not based on HTTP/REST such as Thrift, we can use the protocol level ‘Interface Definition Languages(IDL)’ (e.g.: Thrift IDL).

Integrating Microservices (Inter-service/process Communication)

In Microservices architecture, the software applications are built as a suite of independent services. So, in order to realize a business use case, it is required to have the communication structures between different microservices/processes. That’s why inter-service/process communication between microservices is a such a vital aspect.

In SOA implementations, the inter-service communication between services is facilitated with an Enterprise Service Bus(ESB) and most of the business logic resides in the intermediate layer (message routing, transformation and orchestration). However, Microservices architecture promotes to eliminate the central message bus/ESB and move the ‘smart-ness’ or business logic to the services and client(known as ‘Smart Endpoints’).

Since microservices use standard protocols such as HTTP, JSON etc. the requirement of integrating with disparate protocol is minimal when it comes to the communication among microservices. Another alternative approach in Microservice communication is to use a lightweight message bus or gateway with minimal routing capabilities and just acting as a ‘dumb pipe’ with no business logic implemented on gateway. Based on these styles there are several communication patterns that has emerged in microservices architecture.

Point-to-point style — Invoking services directly

In point to point style, the entire the message routing logic resides on each endpoint and the services can communicate directly. Each microservice exposes a REST APIs and a given microservice or an external client can invoke another microservice through its REST API.

Figure 4 : Inter-service communication with point-to-point connectivity.

Obviously this model works for relatively simple microservices based applications but as the number of services increases, this will become overwhelmingly complex. After-all that’s the exact same reason for using ESB in the traditional SOA implementation which is to get rid of this messy point-to-point integration links. Let’s try to summarize the key drawbacks of the point-to-point style for microservice communication.

The non-functional requirements such as end-user authentication, throttling, monitoring etc. has to be implemented at each and every microservice level.

As a result of duplicating common functionalities, each microservice implementation can become complex.

There is no control what so ever on the communication between the services and clients (even for monitoring, tracing or filtering)

Often the direct communication style is considered as an microservice anti-pattern for large scale microservice implementations.

Therefore, for complex Microservices use cases, rather than having point-to-point connectivity or a central ESB, we could have a lightweight central messaging bus which can provide an abstraction layer for the microservices and that can be used to implement various non-functional capabilities. This style is known as API Gateway style.

API-Gateway style

The key idea behind the API Gateway style is that using a lightweight message gateway as the main entry point for all the clients/consumers and implement the common non-functional requirements at the Gateway level. In general an API Gateway allows you to consume a managed API over REST/HTTP. Therefore, here we can expose our business functionalities which are implemented as microservices, through the API-GW, as managed APIs. In fact, this is a combination of Microservices architecture and API-Management which give you the best of both worlds.

Figure 5: All microservices are exposed through an API-GW.

In our retail business scenario, as depicted in figure 5, all the microservices are exposed through an API-GW and that is the single entry point for all the clients. If a microservice wants to consume another microservice that also needs to be done through the API-GW.

API-GW style gives you the following advantages.

Ability to provide the required abstractions at the gateway level for the existing microservices. For example, rather than provide a one-size-fits-all style API, the API gateway can expose a different API for each client.

Lightweight message routing/transformations at gateway level.

Central place to apply non-functional capabilities such as security, monitoring and throttling.

With the use of API-GW pattern, the microservice become even more lightweight as all the non-functional requirements are implemented at the Gateway level.

The API-GW style could well be the most widely used pattern in most microservice implementations.

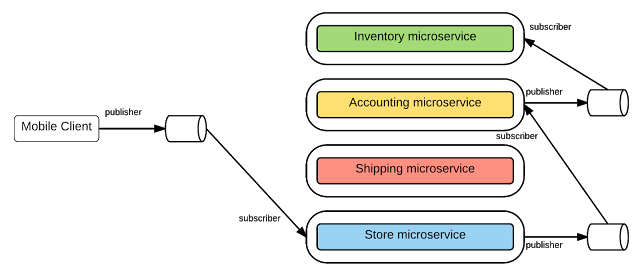

Message Broker style

The microservices can be integrated in asynchronous messaging scenario such as one-way requests and publish-subscribe messaging using queues or topics. A given microservice can be the message producer and it can asynchronously send message to a queue or topic. Then the consuming microservice can consume messages from the queue or topic. This style decouples message producers from message consumers and the intermediate message broker will buffer messages until the consumer is able to process them. Producer microservices are completely unaware of the consumer microservices.

Figure 6 : Asynchronous messaging based integration using pub-sub.

The communication between the consumers/producers is facilitated through a message broker which is based on asynchronous messaging standards such as AMQP, MQTT etc.

Decentralized Data Management

In monolithic architecture the application stores data in a single and centralized databases to implement various functionalities/capabilities of the application.

Figure 7 : Monolithic application uses a centralized database to implement all its features.

In Microservices architecture the functionalities are disperse across multiple microservices and if we use the same centralized database, then the microservices will be no longer independent from each other (for instance, if the database schema has changed from a given microservice, that will break several other services). Therefore each microservice has to have its own database.

Figure 8 : Microservices has its own private database and they can’t directly access the database owned by other microservices.

Here are the key aspect of implementing de-centralized data management in microservices architecture.

Each microservice can have a private database to persist the data that requires to implement the business functionality offered from it.

A given microservice can only access the dedicated private database but not the databases of other microservices.

In some business scenarios, you might have to update several database for a single transaction. In such scenarios, the databases of other microservices should be updated through its service API only (not allowed to access the database directly)

The de-centralized data management give you the fully decoupled microservices and the liberty of choosing disparate data management techniques (SQL or NoSQL etc., different database management systems for each service). However, for complex transactional use cases that involves multiple microservices, the transactional behavior has to be implemented using the APIs offered from each service and the logic resides either at the client or intermediary (GW) level.

Decentralized Governance

Microservices architecture favors decentralized governance.

In general ‘governance’ means establishing and enforcing how people and solutions work together to achieve organizational objectives. In the context of SOA, SOA governance guides the development of reusable services, establishing how services will be designed and developed and how those services will change over time. It establishes agreements between the providers of services and the consumers of those services, telling the consumers what they can expect and the providers what they’re obligated to provide. In SOA Governance there are two types of governance that are in common use:

Design-time governance — defining and controlling the service creations, design and implementation of service policies

Run-time governance — the ability to enforce service policies during execution

So what does governance in Microservices context, really means? In microservices architecture, the microservices are built as fully independent and decoupled services with the variety of technologies and platforms. So there is no need of defining a common standards for services designing and development. So, we can summarize the decentralized governance capabilities of Microservices as follows.

In microservices architecture there is no requirement to have centralized design-time governance.

Microservices can make their own decisions about its design and implementation.

Microservices architecture foster the sharing of common/reusable services.

Some of the run-time governances aspects such as SLAs, throttling, monitoring, common security requirements and service discovery may be implemented at API-GW level.

Service Registry and Service Discovery

In Microservices architecture the number of microservices that you need to deal with is quite high. And also their locations change dynamically owing to the rapid and agile development/deployment nature of microservices. Therefore you need to find the location of a microservice during the runtime. The solution to this problem is to use a Service Registry.

Service Registry

Service Registry holds the microservices instances and their locations. Microservice instances are registered with the service registry on startup and deregistered on shutdown. The consumers can find the available microservices and their locations through service registry.

Service Discovery

To find the available microservices and their location, we need to have a service discovery mechanism. There are two types of service discovery mechanisms, Client-side Discovery and Server-side Discovery. Let’s have a closer look at those service discovery mechanisms.

Client-side Discovery

In this approach the client or the API-GW obtains the location of a service instance by querying a Service Registry.

Figure 9 — Client-side discovery

Here the client/API-GW has to implement the service discovery logic by calling the Service-Registry component.

Server-side Discovery

With this approach, clients/API-GW sends the request to a component(such as a Load balancer) that runs on a well-known location. That component calls the service registry and determine the absolute location of the microservice.

Figure 10 — Server-side discovery

The microservices deployment solutions such as Kubernetes(http://kubernetes.io/v1.1/docs/user-guide/services.html) offers service-side discovery mechanisms.

Deployment

When it comes to microservices architecture, the deployment of microservices plays a critical role and has the following key requirements.

Ability to deploy/un-deploy independently of other microservices.

Must be able to scale at each microservices level (a given service may get more traffic than other services).

Building and deploying microservices quickly.

Failure in one microservice must not affect any of the other services.

Docker (an open source engine that lets developers and system administrators deploy self-sufficient application containers in Linux environments) provides a great way to deploy microservices addressing the above requirements. The key steps involved are as follows.

Package the microservice as a (Docker) container image.

Deploy each service instance as a container.

Scaling is done based on changing the number of container instances.

The building, deploying and starting microservice will be much faster as we are using Docker containers (which is much faster than a regular VM)

Kubernetes is extending Docker’s capabilities by allowing to manage a cluster of Linux containers as a single system, managing and running Docker containers across multiple hosts, offering co-location of containers, service discovery and replication control. As you can see, most of these features are essential in our microservices context too. Hence using Kubernetes (on top of Docker) for microservices deployment has become an extremely powerful approach, specially for large scale microservices deployments.

Figure 11 : Building and deploying microservices as containers.

In figure 11, it shows an overview of the deployment of the microservices of the retail application. Each microservice instance is deployed as a container and there are two container per each host. You can arbitrary change no of container that you run on a given host.

Security

Securing microservices is a quite common requirement when you use microservices in real-world scenarios. Before jumping in to microservices security let’s have a quick look at how we normally implements security at monolithic application level.

In a typical monolithic application, the security is about finding that ‘who is the caller’, ‘what can the caller do’ and ‘how do we propagate that information’.

This is usually implemented at a common security component which is at the beginning of the request handling chain and that component populates the required information with the use of an underlying user repository (or user store).

So, can we directly translate this pattern into the microservices architecture? Yes, but that requires a security component implemented at each microservices level which is talking to a centralized/shared user repository and retrieve the required information. That’s is a very tedious approach of solving the Microservices security problem.

Instead, we can leverage the widely used API-Security standards such as OAuth2 and OpenID Connect to find a better solution to Microservices security problem. Before dive deep into that let me just summarize the purpose of each standard and how we can use them.

OAuth2 — Is an access delegation protocol. The client authenticates with authorization server and get an opaque token which is known as ‘Access token’. Access token has zero information about the user/client. It only has a reference to the user information that can only be retrieved by the Authorization server. Hence this is known as a ‘by-reference token’ and it is safe to use this token even in the public network/internet.

OpenID Connect behaves similar to OAuth but in addition to the Access token, the authorization server issues an ID token which contains information about the user. This is often implement by a JWT (JSON Web Token) and that is signed by authorization server. So, this ensures the trust between the authorization server and the client. JWT token is therefore known as a ‘By-value token’ as it contains the information of the user and obviously it is not safe to use it outside the internal network.

Now, let's see how we can use these standards to secure microservices in our retail example.

Figure 12 : Microservice security with OAuth2 and OpenID Connect

As shown in figure 12, these are the key steps involved in implementing microservices security.

Leave authentication to OAuth and the OpenID Connect server(Authorization Server), so that microservices successfully provide access given someone has the right to use the data.

Use the API-GW style, in which there is a single entry point for all the client request.

Client connects to authorization server and obtains the Access Token (by-reference token).Then send the access token to the API-GW along with the request.

Token Translation at the Gateway — API-GW extracts the access token and send it to the authorization server to retrieve the JWT (by value-token).

Then GW passes this JWT along with the request to the microservices layer.

JWTs contains the necessary information to help in storing user sessions etc. If each service can understand a JSON web token, then you have distributed your identity mechanism which is allowing you to transport identity throughout your system.

At each microservice layer, we can have a component that process the JWT, which is a quite trivial implementation.

Transactions

How about the transactions support in microservices? In fact, supporting distributed transactions across multiple microservices is an exceptionally complex task. The microservice architecture itself encourages the transaction-less coordination between services.

The idea is that, a given service is fully self-contained and based on the single responsibility principle. The need to have distributed transaction across multiple microservces is often a symptom of a design flaw in microservice architecture and usually can be sorted out by refactoring the scopes of microservices.

However, if there is a mandatory requirement to have distributed transactions across multiple services, then such scenarios can be realized with the introduction of ‘compensating operations’ at each microservice level. The key idea is, a given microservice is based on the single responsibility principle and if a given microservice failed to execute a given operation, we can consider that as a failure of that entire microservice. Then all the other (upstream) operations has to be undone by invoking the respective compensating operation of those microservice.

Design for Failures

Microservice architecture introduces dispersed set of services and compared to monolithic design, that increases the possibility of having failures at each service level. A given microservice can fail due to network issues, unavailability of the underlying resources etc. An unavailable or unresponsive microservice should not bring the whole microservices-based application down. Thus microservices should be fault tolerant, be able to recover when that is possible and the client has to handle it gracefully.

Also, since services can fail at any time, it’s important to be able to detect(real-time monitoring) the failures quickly and, if possible, automatically restore the services. There are several commonly used patterns in handling errors in Microservices context.

Circuit Breaker

When you are doing an external call to a microservice, you configure a fault monitor component with each invocation and when the failures reach a certain threshold then that component stops any further invocations of the service (trips the circuit). After certain number of requests in open state (which you can configure), change the circuit back to close state.

This pattern is quite useful to avoid unnecessary resource consumption, request delay due to timeouts and also give us to chance to monitor the system (based on the active open circuits states).

Bulkhead

As microservice application comprises of number of microservices, the failures of one part of the microservices-based application should not affect the rest of the application. Bulkhead pattern is about isolating different parts of your application so that a failure of a service in such part of the application does not affect any of the other services.

Timeout

The timeout pattern is a mechanism which is allowing you to stop waiting for a response from the microservice when you think that it won’t come. Here you can configure the time interval that you wish to wait.

So, where and how do we use these patterns with microservices? In most cases, most of these patterns are applicable at the Gateway level. Which means when the microservices are not available or not responding, at the Gateway level we can decide whether to send the request to the microservice using a circuit breaker or timeout pattern. Also, its quite important to have patterns such as bulkhead implemented at the Gateway level as its the single entry point for all the client requests, so a failure in a given service should not affect the invocation of the other microservices.

In addition, Gateway can be used as the central point that we can obtain the status and monitor of each microservice as each microservices is invoked through the Gateway.

Last updated